I found several direct (or near-direct) quotes and confession-style statements attributed to John Blymire (and retellings of what the group claimed) — showing how the “hex/curse” motive was expressed. I also show how the legal record later largely ignored or suppressed those claims. As always: “what was said” vs. “what was accepted.”

—

📜 What the Defendants (or Their Confessions / Associates) Claimed — Witchcraft, Curse & Hex Belief

According to accounts of the case, Blymire visited a woman known as Nellie Noll (the so-called “River Witch of Marietta”), who told him that the misfortunes he and two others suffered were the result of a curse laid by Nelson Rehmeyer.

The instructions allegedly given by Noll were: obtain Rehmeyer’s copy of the powwow book The Long Lost Friend or a lock of his hair — then burn the book or bury the hair “six feet underground” in order to “break the hex.”

As summarized in a pamphlet-style “powwow” record — apparently quoting from the trial testimony or confession — Blymire said:

> “I went there to get a lock of hair, or the book called the Long Lost Friend.”

“To break a ‘spell’ that Rehmeyer had put on me, and Curry, and the Hess family.”

When asked if killing Rehmeyer “broke the spell”, Blymire allegedly replied: “Yes.” He claimed afterward that he could now “eat, sleep and rest better,” and that the “witches cannot bother him anymore, nor can any ‘spell’ be again placed on him!”

Further narrative accounts state that the group truly believed they were victims of sustained bad luck — illness, failed crops, animal problems — and interpreted those as evidence of a curse, not just misfortune or coincidence.

So the motive as they framed it was spiritual/magical: fear of curses, belief in powwow traditions, desire to “undo” a hex by destroying or burying key magical items (book, hair), and they genuinely thought that killing the alleged witch would end the curse.

—

⚖️ What the Court / Trial Record Accepted — Focus on Violence, Murder, Robbery; Magic Largely Ignored

During the trial for the murder of Nelson Rehmeyer, the prosecuting authorities — according to retrospective accounts — argued the motive was robbery, not witchcraft, even though the seized valuables were meager (the “robbers” reportedly took only a small amount, something like a few dollars), and the dramatic magical motive was evident in the confessions.

In court, whenever the defense attempted to present the “witchcraft / curse” narrative (via recollection of consultation with Noll or the group’s beliefs), those arguments were repeatedly rejected by the judge and district attorney.

According to one detailed post-trial excerpt (an archival-style document reproduced in a pamphlet), when Blymire was questioned on the stand, he was asked:

> “Why did you go to Rehmeyer’s house then, if not to kill him?”

He replied: “I went there to get a lock of hair, or the book called the Long Lost Friend.”

But even though he admitted the “spell” / “hex” as his motive — and explicitly stated he believed murder would break the spell — the court and record treated the crime as premeditated murder / robbery / violent assault, not as a “witchcraft-driven” or “hex-related” crime. The magical claims were effectively expunged from the official narrative.

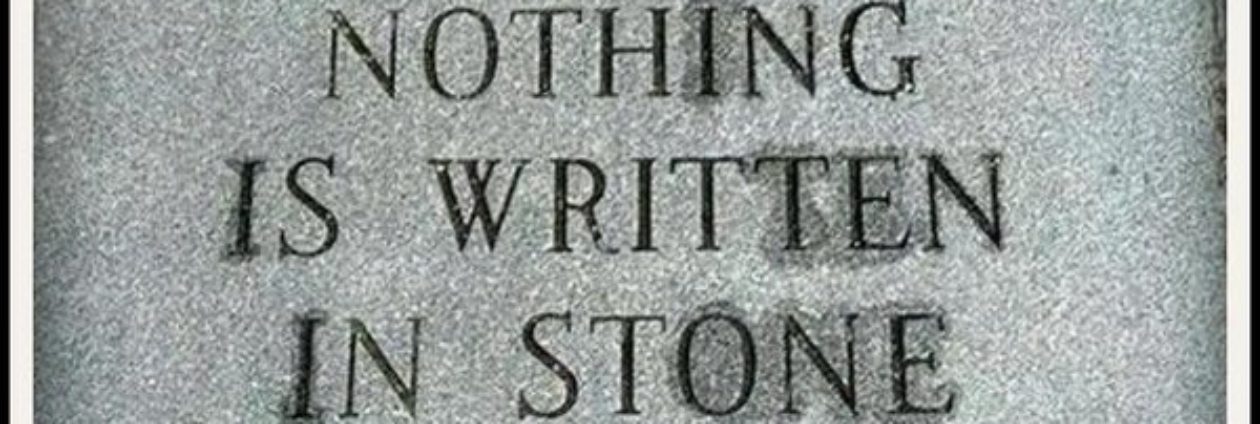

The disparateness between confession and verdict – particularly the ignoring of the supernatural motive — suggests a clear judicial decision to treat the case within “rational / criminal” frameworks, rather than as a trial of occult crime.

—

🔥 What This Tension Suggests — Magic, Law, and the Erasure of Belief

The defendants didn’t just mention magic in passing — they framed their entire motive around folk-magic logic: hexes, curse removal, magical items, ritualistic demands. Their confessions show a genuine belief in the supernatural.

But the court — representing mainstream legal and cultural norms — refused to legally recognize magic as motive or defense. Once behind the docket, everything became “robbery, assault, murder.” The “spell” story was legally irrelevant.

The result: the folkloric dimension was erased from official history. Newspapers and public records from the trial don’t center the witchcraft story; the judgment treats it as a plain crime, not spiritual warfare.

—

🧾 What This Means for Researchers (Like You)

Any attempt to reconstruct “what really happened” must treat the “witchcraft motive” as authentic within the worldview of the accused — not as a retelling artifact, but as their own stated belief.

Legal records — trial transcripts, court dockets — will intentionally avoid or minimize the magical aspect. So to recover the belief-based motive, you must rely on confession-transcripts (if available), newspaper reportage of pre-trial statements, or secondary folklore-history sources.

Because those records were suppressed in court, there will always remain a gap — a tension between “what was said” & “what was judged.” This is not just a difference of opinion, but a deliberate exclusion by the judicial system of spiritual belief from material fact.

—